What’s NXT: The Future of Sustainability

Issues of sustainability have always affected societies, albeit in different shapes and forms. Whether it was the wood crisis that plagued our early industrialization or the ozone crisis, we are constantly dealing with the impacts of our consumption. Now that we have “gone global” since the 1990's, sustainability is taking on an even more complex shape. The next decades will see the emergence of new environmental and sustainability issues. What can we expect in the future?

It might be easy to assume that because geopolitical tensions in the world have resurfaced and that we are entering a period of high uncertainty marked by the emergence of a new multipolar world order, sustainability will be relegated to a low priority objective. Because after all, economic downturns have never been good for environmentalist or sustainability causes. Like always, it’s a bit more complex. Here are eight trends in the field of sustainability.

Trend 1: From costs to risks (and opportunities!)

With a growing realization by the public and decision makers that the climate crisis is happening right now, it has taken on a newer, more existential survival-oriented dimension. When the German insurer Munich Re estimates costs of $40 billion for reparations after the 2021 floods in western Germany, the magnitude and prospects of future natural disasters are starting to be a cumbersome reality for governments and private corporations alike.

The desire to avoid these types of events have increasingly led companies to focus on ways to minimize risk which is perhaps best identified by the rise of ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) reporting. Though still in its early days, ESG reporting is aiming to turn the previously non-financially related matters into issues of importance for the long-term well-being of a company, and the challenge is to turn this qualitative information into quantitative data.

Risk management means avoiding things like child labor, deforestation practices and increasingly, fossil fuels. It always means weighing those risks against each other. H&M’s decision to stop buying cotton from the Xinjiang province in China is just one example. In 2019, the European Investment Bank, one of the world’s largest lenders, even went as far as declaring that they would end financing for fossil fuel projects by 2021 and thus align themselves with the Paris agreement.

In all this risk minimizing, we are also seeing the rise of opportunities. Companies cultivating their brand identity around activism, such as Patagonia, have benefited from the general atmosphere that something needs to be done. They’ve also inspired other companies by showing that profitability need not be sacrificed because of standing up for a cause.

Another downstream effect has been shorter, and more concentrated supply chains who have become more desirable in this risk reducing environment. Getting rid of subcontractors and moving production closer to headquarters has become a new trend. This is perhaps particularly well illustrated in the case of semiconductors, where both the EU and US are actively seeking to become less reliant on chip imports.

Trend 2: From the parts to the sum

Getting a systems perspective is, admittedly, something organizations are struggling with in general. Regarding sustainability however, things are looking brighter. According to the Global Reporting Initiative, most organizations today – both public and private – are finding creative ways to relate to and take action on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Most are not only providing insights on their sustainability work in their yearly sustainability reports but are also actively showcasing their progress on their websites.

What this creates is an environment where actors go from showing THAT they work with sustainability, to increasingly having to compete on grounds of HOW they work with sustainability. And that’s where things really get impactful, that is, when performing well becomes a success criterion – especially as the number of actors evaluating sustainability performance is increasing and the regulatory environment growing stricter.

ESG reporting is, again, a sign of this. The mounting requirements to measure more and more complex forms of emissions – scope 3 (indirect emissions) or even scope 4 (avoided emissions) – the ones that are located both upstream and downstream is yet another sign of tying together of knots along the chain.

What we can expect to see after this is likely the converting of all this impact data to financial metrics. There are already signs, such as the social cost of carbon used by the American administration – a way to quantify in dollars all the numerous ways in which emissions cause damage to people, property, productivity and beyond. Carbon has a cost, and that cost needs to be better understood. But beware of the so-called carbon-tunnel-syndrome: there will be more areas in need of quantification – think of biodiversity.

Trend 3: From politics to companies and finance

This third trend is about the widespread adoption of sustainability initiatives. What started off as research has transitioned to government objectives and, more recently, private sector competition and collaboration. The UN led coalition Race to Zero brings together actors representing over 50% of the worlds GDP and 25% of global emissions. Similarly, the Science Based Targets Initiative is helping companies set and engage with emission reduction best practices and provide technical assistance.

While not all companies are onboard, even large financial institutions have demonstrated a clear direction. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund and the Rockefeller foundation are just two examples of large financial actors who have divested from oil and gas. Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager also announced in 2020 that sustainability would be central to their investing strategy and sought to position itself as a leader in climate neutrality.

Trend 4: From problems to solutions (and obstacles)

Increasingly, climate change is turning into a new type of moon-race: a clear goal, due-date, and consensus but the rest to figure out. There is a growing sense of urgency, more actors getting onboard as well as the development of new technologies – all this combined with a necessity to show how one addresses sustainability. These are indicators that we have entered the solution phase. In other words, it goes from existentially complex, to practically doable.

Dramatically lower costs for renewables and batteries are making it possible to envision a path forward. The rapidly growing cost of CO2 is now making carbon capture and storage (CCUS) profitable across many industries. And so, the way gets clearer and drives more actors to innovate around solutions and thus, more opportunities.

While all this surely provides a positive momentum, it also highlights some new obstacles. The difference is that those obstacles tend to be of a technical nature. Another way to view this in the context of carbon capture is that we go from asking questions like “How can we remove all this carbon?” to questions like “Should the carbon be captured at source point or directly in the air?”. The latter is radically easier for one actor to address.

Trend 5: From small-scale initiatives to megaprojects

The transition to climate neutral and sustainable economies is not going to be cheap: it requires serious investments. To get there now by phasing out fossil-fuels would require us to build one nuclear power plant a day up to 2050, as our energy consumption is expected to increase by 1,25% per year according the International Energy Agency. A joint report by the OECD, the World Bank and the UNEP found that 9% of global GDP are needed for the road to zero to reach its destination.

Needless to say, the amount needed for this historical reorganization of our relation to energy is huge – and huge is perhaps an understatement. As striking as this may be, we are witnessing the momentum build up as megaprojects are starting to emerge. Everywhere from the private to the public sector, gigantic plans are in the works.

We are seeing signals everywhere around us: Volkswagen is investing €35 billion in electric vehicles over the next 5 years. A few weeks ago, investment firm Apollo announced it would deploy $50 billion in clean energy and climate capital. Public policy too is showing its desire to stimulate innovation and action: the European Green Deal is mobilizing over €1 trillion over the next 10 years.

Trend 6: From client & contractor to integrated partnerships

Our supplies chains are complex. The average car consists of approximately 30 000 parts that are generally manufactured by different contractors in different countries. As the regulatory environment is getting stricter and as companies are increasingly obligated to report on downstream emissions, actors in these supply chains are faced with few options: work together and simplify open data sharing or work alone and do everything yourself. Larger companies, cities and nations will need to help their subcontractors to help themselves.

In general, though, tracking emissions and other climate related data through supply chains will necessitate robust collaboration between researchers, consultants, manufacturers, etc. ESG metrics will need to go from being qualitative to become more quantifiable and thus dramatically challenge the way data is shared across the value chain.

Trend 7: From executive & legislative to judiciary action

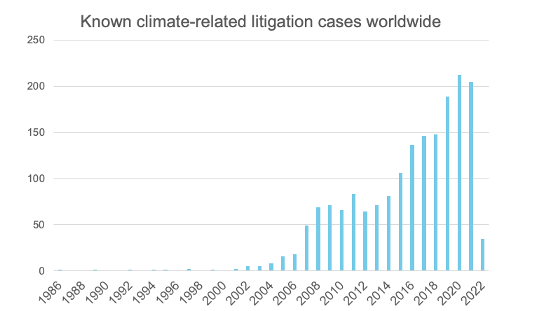

The number of legal cases against governments and corporations is increasing at a remarkable rate. While previously in the realm of the executive and legislative power, we are now seeing legal action taken around the world on the basis of climate science and targets. Companies and governments that are failing to meet their national targets are now being brought to court.

Source: Climate Change Litigation Databases, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

The 2015 Paris Agreement helped fuel this trend by setting clear governmental targets focused on keeping global temperatures to well below 2°C over pre-industrial levels. Because the science in emission quantification is advancing, it is now possible to determine whether an organization’s own targets are compatible with the boarder Paris framework. This trend will likely keep growing as more and more countries are making the agreement into national laws and the quality of climate modelling improves further.

Many cases worldwide have set intriguing precedents for what we can expect in the coming future. In Poland, an environmental organization was able to successfully prevent an energy company from building another coal power plant, which will likely result in the end of new coal plants in the country. After a court ruling in the Netherlands, oil giant Shell was ordered to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030 and found that it was responsible for the emissions of its clients (scope 3). We can probably expect a lot more of these cases as IPCC reports are getting increasingly alarming.

Trend 8: Sustainability goes geopolitical

One of the final transformations we expect sustainability to undergo is its merger with geopolitical issues. What exactly happens when sustainability becomes a matter of national security and strategy?

First off, why should they even become one? Fundamentally, it is about the strategic use of resources and any society making extensive use of natural resource for its development is bound to care about how the availability of these resources is affected. For societies to continue developing, they also need to ensure that the environment they are developing in remains stable and predictable. Climate change creates the opposite situation by increasing unpredictability and risk and destabilizing global dynamics.

In a sense then, it has always been geopolitical, but now that our growing understanding that the world of tomorrow will be a world centered around low carbon technology, everyone is rushing to be a key player. But the transition requires a lot of new materials – most famously perhaps are cobalt, lithium, and rare earth minerals. Not only will those be needed in exponential quantities over the next decades, but they are also even more concentrated in the hands of a few key players.

The great thing about many of these resources is that if they are recycled properly, the vast majority of them have impressive recovery rates – making the vision and possibility of a circular economy much more realistic.

So, what should you remember?

First there are the eight trends:

Trend 1: From Costs to Risks (and Opportunities!)

Trend 2: From the Parts to the Sum

Trend 3: From Politics to Companies and Finance

Trend 4: From Problems to Solutions (and Obstacles)

Trend 5: From Small-scale Initiatives to Megaprojects

Trend 6: From Client & Contractor to Integrated Partnerships

Trend 7: From Executive & Legislative to Judiciary Action

Trend 8: Sustainability Goes Geopolitical

Because the future will always be about how efficiently we can use our resources and adapt to the challenges that constrain our development, the organizations that will lead the way are those who understand this phenomenon well and make sustainability their competitive edge.

Read more in this article (in Swedish) by Kairos Future Founder Mats Lindgren.

The strategic challenges that the sustainability transition pose to organizations is as ambitious as it is historical. For 30 years, Kairos Future has been assisting organizations and leaders in understanding and shaping their world. If you need help in making sense of this future low-carbon economy or strategic advice, feel free to reach out to Mats Lindgren.